In today’s complex world, the ability to navigate challenges, understand different perspectives, and collaborate on solutions is more critical than ever. For educators and parents, fostering these skills goes beyond academic instruction; it requires equipping students with practical social-emotional learning (SEL) tools. To move beyond worksheets and focus on building resilient young problem-solvers, educators can leverage strategies like Problem Based Learning, which challenges students to solve real-world problems. This approach sets the stage for deeper, more meaningful engagement.

This article provides a curated collection of ten powerful, classroom-ready problem-solving activity models designed for K–8 students. Each entry is a deep dive, offering not just a concept but a comprehensive guide. You will find step-by-step instructions, practical examples for teachers and parents, differentiation tips, and clear connections to core SEL competencies.

We will explore a range of powerful techniques, from the analytical Five Whys and Fishbone Diagrams to the empathetic practices of Restorative Circles and Empathy Mapping. You’ll discover how to implement structured dialogue with protocols like Brave Space Conversations and Collaborative Problem-Solving. The goal is to provide actionable frameworks you can use immediately to build a more connected, empathetic, and resilient school community. These aren’t just activities; they are frameworks for transforming your classroom or home into a dynamic space for growth, aligning with Soul Shoppe’s mission to help every child thrive. Let’s explore how these proven strategies can empower your students.

1. The Five Whys Technique

The Five Whys technique is a powerful root-cause analysis tool that helps students and educators move past surface-level issues to understand the deeper, underlying reasons for a problem. By repeatedly asking “Why?” (typically five times), you can peel back layers of a situation to uncover the core issue, which is often emotional or social. This problem solving activity is excellent for addressing conflicts, behavioral challenges, and social dynamics in a way that fosters empathy and genuine understanding.

This method transforms how we approach discipline, shifting the focus from punishment to support. Instead of simply addressing a behavior, we seek to understand the unmet need driving it.

How It Works: A Classroom Example

Imagine a student, Alex, consistently fails to turn in his math homework. A surface-level response might be detention, but using the Five Whys reveals a more complex issue.

- Why didn’t you turn in your homework? “I didn’t do it.” (The initial problem)

- Why didn’t you do it? “I didn’t understand how.” (Reveals a skill gap, not defiance)

- Why didn’t you ask for help? “I was afraid to look dumb in front of everyone.” (Uncovers social anxiety)

- Why were you afraid of looking dumb? “Last time I asked a question, some kids laughed at me.” (Identifies a past negative social experience)

- Why do you think they laughed? “Maybe they don’t like me or think I’m not smart.” (Pinpoints the root cause: a feeling of social isolation and a need for belonging)

This process reveals that the homework issue is not about laziness but about a need for a safe and inclusive classroom environment. The solution is no longer punitive but focuses on building community and providing discreet academic support.

Key Insight: The Five Whys helps us see that behavior is a form of communication. By digging deeper, we can address the actual need instead of just reacting to the symptom.

Tips for Implementation

- Create a Safe Space: This technique requires trust. Ensure the conversation is private and framed with genuine curiosity, not interrogation. Start by saying, “I want to understand what’s happening. Can we talk about it?”

- Model the Process: Teach students the Five Whys method directly. Use it to solve classroom-wide problems, like a messy coatroom, so they learn how to apply it themselves. Practical Example: A teacher might say, “Our coatroom is always a mess. Why? Because coats are on the floor. Why? Because the hooks are full. Why? Because some people have multiple items on one hook. Why? Because there aren’t enough hooks for our class. Why? Because our class size is larger this year.” The root cause is a lack of resources, not student carelessness.

- Be Flexible: Sometimes you may need more or fewer than five “whys” to get to the root cause. The goal is understanding, not adhering strictly to the number.

For more tools on building a supportive classroom culture where this problem solving activity can thrive, explore our Peace Corner resources.

2. Fishbone Diagram (Ishikawa Diagram)

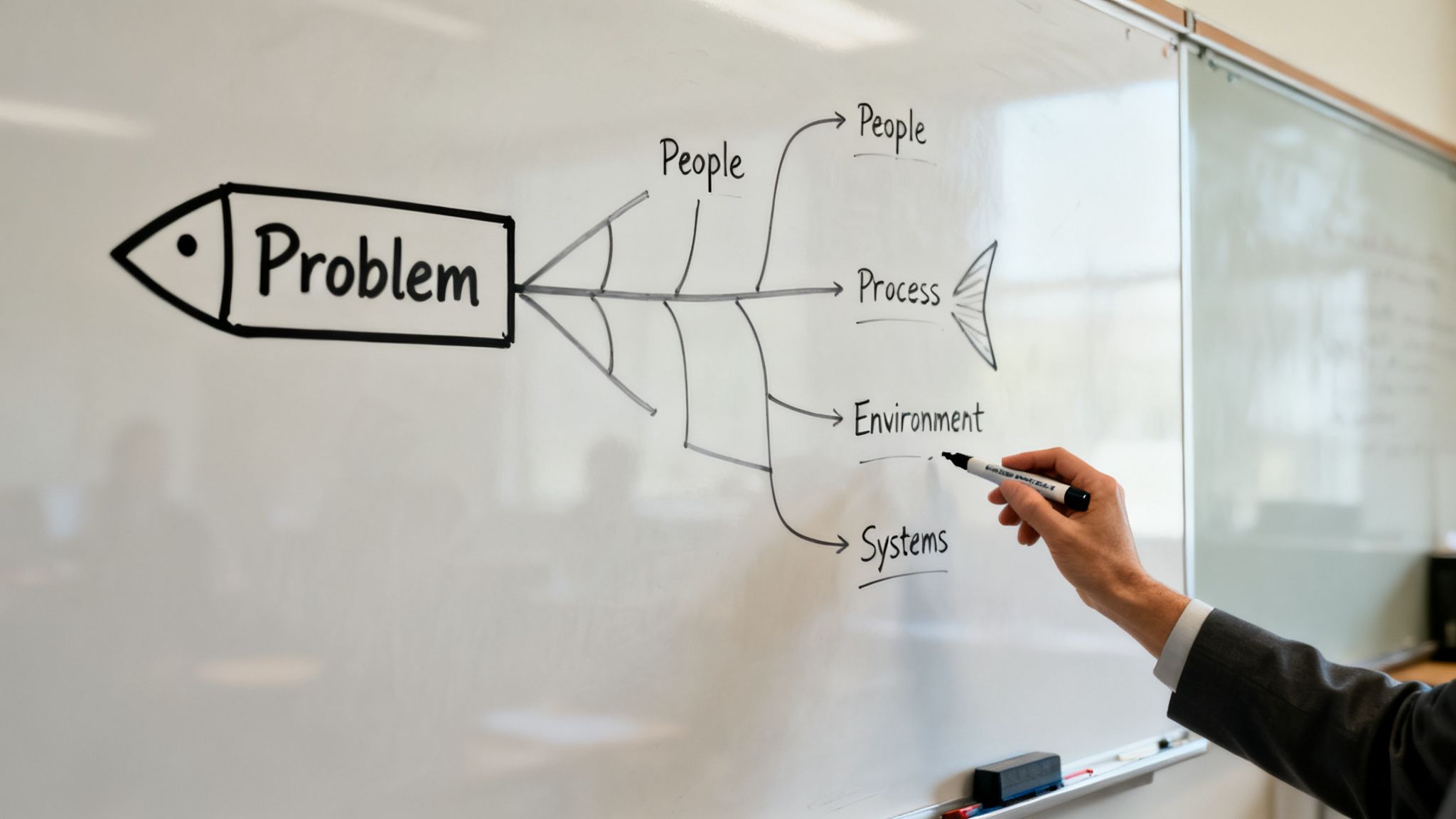

The Fishbone Diagram, also known as an Ishikawa or Cause and Effect Diagram, is a visual tool that helps groups brainstorm and map out the potential causes of a specific problem. Its structure resembles a fish skeleton, with the “head” representing the problem and the “bones” branching out into categories of potential causes. This problem solving activity is ideal for unpacking complex, multi-faceted issues like bullying, student disengagement, or chronic classroom disruptions.

It encourages collaborative thinking and prevents teams from jumping to a single, simplistic conclusion. Instead, it systematically organizes potential factors into logical groups, making it easier to see how different elements contribute to the central issue.

How It Works: A School-Wide Example

Imagine a school is struggling with low student engagement during Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) blocks. The problem statement at the “head” of the fish is: “Students are disengaged during SEL time.” The team then brainstorms causes under key categories.

- Instruction (Methods): Lessons are not culturally relevant; activities are repetitive; delivery is lecture-based rather than interactive.

- Environment (Setting): Classroom setup doesn’t support group work; SEL is scheduled right before lunch when students are restless.

- People (Students/Staff): Staff lack confidence in teaching SEL topics; students don’t see the value or feel it’s “not cool.”

- Resources (Materials): The curriculum is outdated; there are not enough materials for hands-on activities.

By mapping these factors, the school can see that the issue is not just one thing. The solution must address curriculum updates, teacher training, and scheduling changes. To help visualize potential causes for a problem, explore more detailed examples of Cause and Effect Diagrams.

Key Insight: Complex problems rarely have a single cause. The Fishbone Diagram helps teams see the interconnectedness of issues and develop more comprehensive, effective solutions.

Tips for Implementation

- Be Specific: Start with a clear and concise problem statement. “Why do 4th graders have frequent conflicts during recess?” is much more effective than a vague statement like “Students are fighting.”

- Involve Diverse Voices: Include teachers, students, counselors, and support staff in the brainstorming process to gain a 360-degree view of the problem.

- Customize Your Categories: While traditional categories exist (like People, Process, etc.), adapt them to fit your school’s context. You might use categories like Policies, Peer Culture, Physical Space, and Family Engagement. Practical Example: For the problem “Students are frequently late to school,” a parent-teacher group might use categories like: Home Factors (alarms, morning routines), Transportation (bus delays, traffic), School Factors (boring first period, long entry lines), and Student Factors (anxiety, lack of motivation).

- Focus on Action: After completing the diagram, have the group vote on the one or two root causes they believe have the biggest impact. This helps prioritize where to direct your energy and resources.

3. Design Thinking Workshops

Design Thinking is a human-centered problem-solving framework that fosters innovation through empathy, collaboration, and experimentation. This problem solving activity guides students and educators to develop creative solutions for complex school challenges, from social dynamics to classroom logistics, by focusing on the needs of the people involved. It builds skills in critical thinking, communication, and resilience.

This approach shifts the focus from finding a single “right” answer to exploring multiple possibilities through an iterative process of understanding, ideating, prototyping, and testing. It empowers students to become active agents of positive change in their own community.

How It Works: A School Example

Imagine a group of students is tasked with improving the cafeteria experience, which many find chaotic and isolating. Instead of administrators imposing new rules, students use design thinking to create their own solutions.

- Empathize: Students conduct interviews and observations. They talk to peers who feel lonely, kitchen staff who feel rushed, and supervisors who feel stressed. They discover the long lines and lack of assigned seating are key pain points.

- Define: The group synthesizes their research into a clear problem statement: “How might we create a more welcoming and efficient lunch environment so that all students feel a sense of belonging?”

- Ideate: The team brainstorms dozens of ideas without judgment. Suggestions range from a “talk-to-someone-new” table and a pre-order lunch app to music playlists and better line management systems.

- Prototype: They decide to test the “conversation starter” table idea. They create a simple sign, a few icebreaker question cards, and ask for volunteers to try it out for a week.

- Test: The team observes the prototype in action, gathers feedback from participants, and learns what works and what doesn’t. They discover students love the idea but want more structured activities. They iterate on their design for the next phase.

This process results in a student-led solution that directly addresses the community’s needs, building both empathy and practical problem-solving skills.

Key Insight: Design Thinking teaches that the best solutions come from deeply understanding the experiences of others. Failure is reframed as a valuable learning opportunity within the iterative process.

Tips for Implementation

- Start with Curiosity: Frame the problem as a question, not a foregone conclusion. Begin with genuine interest in understanding the experiences of those affected without having a solution in mind.

- Encourage ‘Yes, And…’ Thinking: During the ideation phase, build on ideas instead of shutting them down. This fosters a creative and psychologically safe environment where all contributions are valued.

- Prototype with Low-Cost Materials: Prototypes don’t need to be perfect. Use cardboard, sticky notes, role-playing, and sketches to make ideas tangible and testable quickly and cheaply. Practical Example: To improve hallway traffic flow, students could create a small-scale model of the hallways using cardboard and use figurines to test different solutions like one-way paths or designated “fast” and “slow” lanes before proposing a change to the school.

For structured programs that help build the collaborative skills needed for design thinking, explore our Peacekeeper Program.

4. Restorative Practices and Peer Mediation

Restorative Practices and Peer Mediation offer a powerful framework for resolving conflict by focusing on repairing harm rather than assigning blame. This approach shifts the goal from punishment to accountability, healing, and reintegration. As a problem solving activity, it teaches students to take responsibility for their actions, understand their impact on others, and work collaboratively to make things right. It is especially effective for addressing complex issues like bullying and significant peer disagreements.

This method builds a stronger, more empathetic community by involving all affected parties in the solution. It empowers students to mend relationships and rebuild trust on their own terms.

How It Works: A Classroom Example

Imagine a conflict where a student, Maria, spread a hurtful rumor about another student, Sam. Instead of just sending Maria to the principal’s office, a peer mediation session is arranged. A trained student mediator facilitates the conversation.

- Setting the Stage: The mediator establishes ground rules for respectful communication. Each student agrees to listen without interrupting and speak from their own experience.

- Sharing Perspectives: The mediator first asks Sam to share how the rumor affected him. He explains that he felt embarrassed and isolated. Then, Maria is given a chance to explain her side.

- Identifying Needs: The mediator helps both students identify what they need to move forward. Sam needs an apology and for the rumor to be corrected. Maria needs to understand why her actions were so hurtful and wants to be forgiven.

- Creating an Agreement: Together, they create a plan. Maria agrees to privately tell the friends she told that the rumor was untrue and to apologize directly to Sam. Sam agrees to accept her apology and move on.

This process resolves the immediate conflict and equips both students with skills to handle future disagreements constructively.

Key Insight: Restorative practices teach that conflict is an opportunity for growth. By focusing on repairing harm, we build accountability and strengthen the entire community.

Tips for Implementation

- Invest in Training: Thoroughly train both staff facilitators and student peer mediators. This training should cover restorative philosophy, active listening, and managing difficult conversations.

- Use Proactively: Don’t wait for harm to occur. Use community-building circles regularly to build relationships and establish a culture of trust and open communication. Practical Example: A teacher can start each week with a “check-in” circle, asking students to share one success and one challenge from their weekend. This builds trust so that when a conflict arises, the circle format is already familiar and safe.

- Establish Clear Protocols: Define when to use peer mediation versus a staff-led restorative conference. More serious incidents may require adult intervention.

- Follow Up: Always check in with the involved parties after an agreement is made to ensure it is being honored and to offer further support if needed.

For a deeper dive into this transformative approach, you can explore what restorative practices in education look like in more detail and learn how to implement them in your school.

5. Mindfulness and Breathing Pause Exercises

Mindfulness and Breathing Pause Exercises are structured practices that teach students to pause, notice their thoughts and emotions, and respond intentionally rather than react impulsively. These techniques create the mental space needed for effective problem-solving by supporting self-regulation and reducing reactive conflict. This problem solving activity is foundational, as it equips students with the internal tools to manage stress before tackling external challenges.

This approach transforms classroom management by empowering students to become active participants in their own emotional regulation. Instead of teachers managing behavior, students learn to manage themselves, which is a critical life skill.

How It Works: A Classroom Example

Consider a common scenario: two students, Maria and Leo, are arguing over a shared tablet. Emotions are escalating, and the argument is about to become a disruptive conflict. Instead of intervening immediately, the teacher initiates a pre-taught “Pause and Breathe” protocol.

- The Trigger: The students begin raising their voices.

- The Pause: The teacher calmly says, “Let’s take a Pause and Breathe.” Both students know this signal. They stop talking, place a hand on their belly, and take three slow, deep breaths.

- Noticing: During these breaths, they shift their focus from the conflict to their physical sensations. They notice their fast heartbeat and tense shoulders. This brief moment of awareness interrupts the reactive emotional spiral.

- Responding: After the pause, the teacher asks, “What do you both need right now?” Having calmed down, Maria can articulate, “I need to finish my turn,” and Leo can say, “I’m worried I won’t get a chance.”

- The Solution: The problem is now reframed from a fight to a scheduling issue. The students can now work with the teacher to create a fair plan for sharing the tablet.

The breathing pause didn’t solve the problem directly, but it created the necessary calm and clarity for the students to engage in a constructive problem solving activity.

Key Insight: A regulated brain is a problem-solving brain. Mindfulness provides the essential first step of calming the nervous system so higher-order thinking can occur.

Tips for Implementation

- Model and Co-Regulate: Practice these exercises with your students daily. Your calm presence is a powerful teaching tool. Never use a breathing exercise as a punishment.

- Start Small: Begin with just one minute of “belly breathing” or a “listening walk” to notice sounds. Gradually build up duration and complexity as students become more comfortable.

- Create a Ritual: Integrate a brief breathing exercise into daily routines, like after recess or before a test, to make it a normal and expected part of the day.

- Connect to Emotions: Explicitly link the practice to real-life situations. Say, “When you feel that big wave of frustration, remember how we do our box breathing. That’s a tool you can use.” Practical Example: Before a math test, a teacher can lead the class in “4×4 Box Breathing”: breathe in for a count of 4, hold for 4, breathe out for 4, and hold for 4. This helps calm test anxiety and improve focus.

For more ideas on integrating these practices, explore our guide on mindfulness exercises for students.

6. The Ladder of Inference (Assumption Analysis)

The Ladder of Inference is a thinking tool that helps students understand how they jump to conclusions. It illustrates the mental process of using selected data, interpreting it through personal beliefs, and forming assumptions that feel like facts. This problem solving activity is invaluable for deconstructing conflicts, misunderstandings, and hurtful situations by revealing the flawed thinking that often fuels them.

This method teaches students to slow down their reasoning and question their interpretations. Instead of reacting to a conclusion, they learn to trace their steps back down the ladder to examine the observable facts, making them more thoughtful communicators and empathetic friends.

How It Works: A Classroom Example

Imagine a student, Maya, sees her friend Chloe whisper to another student and then laugh while looking in her direction. Maya quickly climbs the ladder of inference and concludes Chloe is making fun of her, leading her to feel hurt and angry.

- The Conclusion: “Chloe is a mean person and not my friend anymore.” (An action or belief)

- The Assumption: “She must be telling a mean joke about me.” (An assumption based on the interpretation)

- The Interpretation: “Whispering and laughing means they are being secretive and unkind.” (Meaning is added based on personal beliefs)

- The Selected Data: Maya focuses only on the whisper, the laugh, and the glance in her direction. She ignores other data, like Chloe smiling at her earlier.

- The Observable Reality: Chloe whispered to another student. They both laughed. They glanced toward Maya. (Just the facts)

By working back down the ladder, Maya can see her conclusion is based on a big assumption. The solution is not to confront Chloe angrily but to get curious and gather more data, for example, by asking, “Hey, what was so funny?”

Key Insight: The Ladder of Inference reveals that our beliefs directly influence how we interpret the world. By learning to separate observation from interpretation, we can prevent minor misunderstandings from becoming major conflicts.

Tips for Implementation

- Use Visual Aids: Draw the ladder on a whiteboard or use a printable graphic. Visually mapping out the steps helps students grasp the abstract concept of their own thinking processes.

- Model the Language: Teach students phrases to challenge assumptions. Encourage them to say, “I’m making an assumption that…” or, “The story I’m telling myself is…” This separates their interpretation from objective reality.

- Practice ‘Getting Curious’: Instead of accepting conclusions, prompt students with questions like, “What did you actually see or hear?” and “What’s another possible reason that could have happened?” This builds a habit of curiosity over certainty. Practical Example: A parent sees their child’s messy room and thinks, “He’s so lazy and disrespectful.” Using the ladder, they can go back to the observable data: “I see clothes on the floor and books on the bed.” Then they can get curious: “What’s another possible reason for this?” Perhaps the child was rushing to finish homework or felt overwhelmed. The parent can then ask, “I see your room is messy. What’s getting in the way of cleaning it up?”

For more strategies on fostering mindful communication and emotional regulation, explore our conflict resolution curriculum.

7. Empathy Mapping and Perspective-Taking Exercises

Empathy Mapping is a powerful problem solving activity that guides students to step into someone else’s shoes and understand their experience from the inside out. By visually mapping what another person sees, hears, thinks, and feels, students move beyond simple sympathy to develop genuine empathy. This structured approach helps them analyze conflicts, social exclusion, and diverse viewpoints with greater compassion and insight.

This method transforms interpersonal problems from “me vs. you” into “us understanding an experience.” It builds the foundational social-emotional skills needed for collaborative problem-solving, making it an essential tool for creating a more inclusive and supportive classroom community.

How It Works: A Classroom Example

Imagine a conflict where a student, Maya, is upset because her classmate, Leo, laughed when she tripped during recess. Instead of focusing only on the action, the teacher uses an empathy map to explore both perspectives.

First, Maya maps Leo’s perspective:

- Sees: Maya falling, other kids playing.

- Hears: A loud noise, other kids laughing nearby.

- Thinks: “That looked funny,” or “I hope she’s okay.”

- Feels: Surprised, maybe amused, or a little embarrassed for her.

Then, Leo maps Maya’s perspective:

- Sees: Everyone looking at her on the ground.

- Hears: Laughter from his direction.

- Thinks: “Everyone is laughing at me. I’m so embarrassed. He did that on purpose.”

- Feels: Hurt, embarrassed, angry, and singled out.

This exercise reveals that while Leo’s reaction may have been thoughtless, Maya’s interpretation was rooted in deep feelings of embarrassment and hurt. The problem to solve is not just the laughter, but the impact it had and how to repair the trust between them.

Key Insight: Empathy mapping shows that intention and impact can be very different. Understanding this gap is the first step toward resolving conflicts and preventing future misunderstandings.

Tips for Implementation

- Use Concrete Scenarios: Ground the activity in specific, relatable situations, like a disagreement over a game or feeling left out at lunch. Avoid abstract concepts that are hard for students to connect with.

- Model Vulnerability: Share an appropriate personal example of a time you misunderstood someone’s perspective. This shows that everyone is still learning and creates a safe space for students to be honest.

- Connect Empathy to Action: After mapping, always ask, “Now that we understand this, what can we do to help or make things better?” This turns insight into positive action. Practical Example: After reading a story about a new student who feels lonely, the class can create an empathy map for that character. Then, the teacher can ask, “What could we do in our class to make a new student feel welcome?” This connects the fictional exercise to real-world classroom behavior.

For a deeper dive into fostering these skills, explore our guide to perspective-taking activities.

8. Collaborative Problem-Solving (CPS) Protocol

The Collaborative Problem-Solving (CPS) Protocol, developed by Dr. Ross Greene, is a structured dialogue method that transforms how adults address challenging behaviors in students. It operates on the core belief that “kids do well if they can,” shifting the focus from a lack of motivation to a lack of skills. This non-confrontational problem solving activity involves both the adult and student as equal partners in understanding and solving problems, making it a powerful tool for de-escalating conflicts and building competence.

This approach replaces unilateral, adult-imposed solutions with a joint effort, which reduces power struggles and turns every conflict into a valuable teaching opportunity. It is especially effective for students with social, emotional, and behavioral challenges.

How It Works: A Classroom Example

Consider a student, Maya, who frequently disrupts class during independent reading time by talking to her neighbors. Instead of assigning a consequence, a teacher uses the CPS protocol.

- Empathy Step: The teacher pulls Maya aside when she is calm. “I’ve noticed that during reading time, it seems like you have a hard time staying quiet. What’s up?” The goal is to listen and gather information without judgment. Maya explains she gets bored and the words “get jumbled” after a few minutes.

- Define the Problem Step: The teacher shares their perspective. “I understand it gets boring and difficult. My concern is that when you talk, it makes it hard for other students to concentrate, and for you to practice your reading.”

- Invitation Step: The teacher invites collaboration. “I wonder if there’s a way we can make it so you can get your reading practice done without it feeling so boring, and also make sure your classmates can focus. Do you have any ideas?”

Together, they brainstorm solutions like breaking up the reading time with short breaks, trying an audio book to follow along, or choosing a high-interest graphic novel. They agree to try a 10-minute reading timer followed by a 2-minute stretch break. This solution addresses both Maya’s lagging skill (sustained attention) and the teacher’s concern (classroom disruption).

Key Insight: CPS reframes misbehavior as a signal of an unsolved problem or a lagging skill. By working together, we teach students how to solve problems, rather than just imposing compliance.

Tips for Implementation

- Listen More Than You Talk: The Empathy step is crucial. Your primary goal is to understand the student’s perspective on what is getting in their way. Resist the urge to jump to solutions.

- Be Proactive: Use the CPS protocol when everyone is calm, not in the heat of the moment. This makes it a preventative tool rather than a reactive one.

- Focus on Realistic Solutions: Brainstorm multiple ideas and evaluate them together. A good solution is one that is realistic, mutually satisfactory, and addresses the concerns of both parties.

- Follow Up: Check in later to see if the solution is working. Be prepared to revisit the conversation and adjust the plan if needed. Practical Example for Parents: A parent notices their child always argues about bedtime. Empathy: “I’ve noticed getting ready for bed is really tough. What’s up?” The child might say, “I’m not tired and I want to finish my game.” Define Problem: “I get that. My concern is that if you don’t sleep enough, you’re really tired and grumpy for school.” Invitation: “I wonder if there’s a way for you to finish your game and also get enough rest. Any ideas?” They might co-create a solution involving a 10-minute warning before screen-off time.

To discover more ways to facilitate productive conversations, check out these conflict resolution activities for kids.

9. Brave Space Conversations and Dialogue Protocols

Brave Space Conversations and Dialogue Protocols are structured frameworks that teach students and adults how to navigate sensitive topics, express different viewpoints respectfully, and stay connected during disagreement. These protocols, inspired by works like Difficult Conversations and the Courageous Conversations framework, prioritize psychological safety and shared responsibility. This problem solving activity is essential for addressing bias, building inclusive communities, and maintaining relationships through conflict.

This approach moves beyond “safe spaces,” where comfort is the goal, to “brave spaces,” where the goal is growth through respectful, and sometimes uncomfortable, dialogue. It equips participants with the tools to talk about what matters most, even when it’s hard.

How It Works: A Classroom Example

Imagine a group of middle school students is divided over a current event involving social inequality. Tensions are high, and students are making hurtful comments. Instead of shutting down the conversation, a teacher uses a dialogue protocol.

- Establish Norms: The class co-creates agreements like “Listen to understand, not to respond,” “Assume good intent but address impact,” and “It’s okay to feel uncomfortable.”

- Introduce Sentence Starters: The teacher provides scaffolds to guide the conversation, such as “I was surprised when I heard you say…” or “Can you tell me more about what you mean by…?”

- Facilitate Dialogue: A student shares their perspective on the event. Another student, instead of reacting defensively, uses a sentence starter: “I hear that you feel…, and my perspective is different. For me, I see…”

- Focus on Impact: A student addresses a peer directly but respectfully: “When you said that, it made me feel invisible because my family has experienced this. Can we talk about that?”

- Seek Mutual Understanding: The conversation continues, with the focus shifting from winning an argument to understanding each other’s lived experiences.

This structured process prevents the conversation from devolving into personal attacks and transforms a potential conflict into a powerful learning moment about empathy, perspective-taking, and community.

Key Insight: Brave spaces normalize discomfort as a necessary part of growth. They teach that the goal of difficult conversations isn’t always agreement, but a deeper mutual understanding and respect.

Tips for Implementation

- Establish Psychological Safety First: Before diving in, clarify that the purpose is learning together. Emphasize that vulnerability is a strength and that mistakes are opportunities for growth.

- Co-Create Norms: Involve students in creating the rules for the conversation. This gives them ownership and makes them more likely to hold themselves and their peers accountable.

- Use Scaffolds and Sentence Frames: Provide language tools to help students articulate their thoughts and feelings constructively, especially when emotions are high. Practical Example: Provide a list of sentence frames on the board, such as: “Help me understand your thinking about…”, “The story I’m telling myself is…”, or “I’m curious about why you see it that way.”

- Acknowledge the Discomfort: Start by saying, “This might feel a bit uncomfortable, and that’s okay. It means we are tackling something important.” This normalization reduces anxiety.

To learn more about fostering brave and respectful classroom environments, explore Soul Shoppe’s approach to building school-wide community.

10. Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) Questioning

Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) Questioning is a strengths-based problem solving activity that shifts the focus from analyzing problems to envisioning solutions. Instead of dissecting what’s wrong, this approach uses targeted questions to help students identify their own strengths, resources, and past successes to build a better future. It empowers students by highlighting their capabilities and fostering a sense of agency.

This method is highly effective for interpersonal challenges and building resilience. It moves a student from a “stuck” mindset, where a problem feels overwhelming, to a proactive one focused on small, achievable steps forward.

How It Works: A Classroom Example

Consider a student who feels consistently left out during recess. A traditional approach might focus on why they are isolated, but SFBT questioning builds a path toward connection.

- The Miracle Question: “Imagine you went to sleep tonight, and while you were sleeping, a miracle happened and your recess problem was solved. When you woke up tomorrow, what would be the first thing you’d notice that tells you things are better?” The student might say, “Someone would ask me to play.”

- Identifying Exceptions: “Can you think of a time, even just for a minute, when recess felt a little bit better?” The student may recall, “Last week, I talked to Maria about a video game for a few minutes, and it was okay.” (This highlights a past success).

- Scaling the Situation: “On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is the worst recess ever and 10 is the miracle recess, where are you today?” The student says, “A 3.” The follow-up is key: “What would need to happen to get you to a 4?” They might suggest, “Maybe I could try talking to Maria about that game again.” (This defines a small, concrete step).

This process helps the student create their own solution based on what has already worked, building confidence and providing a clear action to take.

Key Insight: SFBT questioning assumes that students already have the tools to solve their problems. Our job is to ask the right questions to help them discover and use those tools.

Tips for Implementation

- Ask with Genuine Curiosity: Your tone should be supportive and inquisitive, not leading. Frame questions to explore possibilities, such as “What would that look like?” or “How did you do that?”

- Focus on Strengths: Actively listen for and acknowledge the student’s capabilities. When they identify a past success, validate it: “Wow, it sounds like you were really brave to do that.”

- Use Scaling Questions: These questions (e.g., “On a scale of 1-10…”) are excellent for measuring progress and identifying the next small step. The goal isn’t to get to 10 immediately but to move up just one point. Practical Example: A student is overwhelmed by a large project. The teacher asks, “On a scale of 1-10, where 1 is ‘I can’t even start’ and 10 is ‘It’s completely done,’ where are you?” The student says, “A 2, because I chose my topic.” The teacher responds, “Great! What’s one small thing you could do to get to a 3?” The student might say, “I could find one book about my topic.” This makes the task feel manageable.

To see how solution-focused language can be integrated into broader conflict resolution, explore our I-Message and conflict resolution tools.

Top 10 Problem-Solving Activities Comparison

| Method | Implementation complexity | Resource requirements | Expected outcomes | Ideal use cases | Key advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Five Whys Technique | Low — simple, linear process | Minimal — facilitator and quiet space | Surface to root-cause insights; increased reflection | Quick conflict debriefs; individual reflection; classroom incidents | Simple, fast, promotes curiosity and reduced blame |

| Fishbone Diagram (Ishikawa) | Moderate — structured group analysis | Moderate — time, facilitator, visual materials | Comprehensive mapping of contributing factors; systems insight | Recurring schoolwide issues; bullying patterns; program analysis | Visualizes complexity; engages multiple stakeholders |

| Design Thinking Workshops | High — multi-stage, iterative process | High — trained facilitators, time, prototyping materials | Student-driven, tested solutions; enhanced creativity and agency | Reimagining student experience; designing new interventions | Empowers students; encourages prototyping and iteration |

| Restorative Practices & Peer Mediation | High — systemic adoption and sustained practice | High — extensive training, staff time, organizational buy-in | Repaired relationships; reduced recidivism; community accountability | Serious harm events, reintegration, community-building | Restores dignity; builds accountability and community ties |

| Mindfulness & Breathing Pause Exercises | Low — short, repeatable practices | Low — brief time, minimal materials, teacher modeling | Improved self-regulation; reduced stress and reactivity | Daily classroom routines; acute de-escalation moments | Immediate calming effects; easy to scale schoolwide |

| Ladder of Inference (Assumption Analysis) | Moderate — conceptual teaching and practice | Low — training/examples, facilitator guidance | Greater metacognition; fewer snap judgments and misunderstandings | Miscommunications; reflective lessons after conflicts | Reveals thinking patterns; promotes curiosity and verification |

| Empathy Mapping & Perspective-Taking | Moderate — guided activities and debriefs | Moderate — materials, facilitation, time | Increased empathy; shared language about needs and impact | Conflict resolution; inclusion lessons; curriculum integration | Makes empathy concrete; reduces othering and stereotyping |

| Collaborative Problem-Solving (CPS) Protocol | Moderate–High — structured dialogue, stepwise | Moderate — trained staff, time per conversation | Reduced power struggles; improved problem-solving skills | Chronic behavioral challenges; individualized supports | Non-punitive, skill-focused, builds trust between adults and students |

| Brave Space Conversations & Dialogue Protocols | Moderate–High — careful prep and facilitation | Moderate — skilled facilitators, norms, prep time | Improved capacity to handle sensitive topics; stronger norms | Equity discussions; identity-based conflicts; staff dialogues | Enables honest, structured difficult conversations; builds psychological safety |

| Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) Questioning | Low–Moderate — focused questioning skills | Low — skilled questioning, brief sessions | Increased agency; small actionable steps; faster shifts in outlook | Individual counseling; resistant or low-engagement students | Strengths-based, efficient, fosters hope and concrete progress |

Putting Problem-Solving into Practice

The journey from a reactive classroom to a responsive and collaborative community is built one problem solving activity at a time. The ten strategies detailed in this guide, from the analytical Five Whys technique to the empathetic practice of restorative circles, are more than just isolated exercises. They are foundational building blocks for creating a culture where challenges are seen as opportunities for growth, connection, and deeper understanding. Integrating these tools empowers students with a versatile toolkit, preparing them not only for academic hurdles but for the complex social dynamics they navigate daily.

The true power of these activities lies in their consistency and thoughtful application. A one-time Fishbone Diagram workshop can illuminate a specific issue, but embedding this thinking into regular classroom discussions transforms how students analyze cause and effect. Similarly, a single breathing pause can de-escalate a tense moment, but making it a routine transition practice cultivates emotional regulation as a lifelong skill. The goal is to move these strategies from a special event to an everyday habit.

Key Takeaways for Immediate Implementation

To make this transition feel manageable, focus on a few core principles that unite every problem solving activity we’ve explored:

- Make Thinking Visible: Activities like the Ladder of Inference and Empathy Mapping help students externalize their internal thought processes. This visibility allows them to question their assumptions and see situations from multiple viewpoints, reducing misunderstandings that often fuel conflict.

- Prioritize Psychological Safety: For any problem-solving to be effective, students must feel safe to be vulnerable. Brave Space Conversations and Restorative Practices are designed to build this foundation of trust, ensuring every voice is heard and valued without fear of judgment.

- Shift from Blame to Contribution: The core of effective problem-solving is moving away from finding a person to blame and toward understanding the various factors that contributed to a problem. The Fishbone Diagram and Collaborative Problem-Solving (CPS) Protocol are excellent frameworks for this, encouraging shared ownership of both the problem and the solution.

- Empower Student Agency: True mastery comes when students can independently select and use the right tool for the right situation. By introducing a variety of methods, you give them the agency to choose whether a situation calls for deep analysis (Five Whys), creative innovation (Design Thinking), or emotional connection (Peer Mediation).

Actionable Next Steps for Educators and Parents

The path to embedding these skills begins with small, intentional steps. You don’t need to implement all ten strategies at once. Instead, consider this a menu of options to be introduced thoughtfully over time.

- Start with Yourself: Before introducing a new problem solving activity to students, practice it yourself. Try using the Five Whys to understand a recurring personal challenge or the Ladder of Inference to check your assumptions before a difficult conversation with a colleague or family member. Modeling is the most powerful form of teaching.

- Choose a Low-Stakes Entry Point: Begin with an activity that feels accessible and addresses a current need. If classroom transitions are chaotic, introduce Mindfulness and Breathing Pauses. If group projects frequently result in friction, try an Empathy Mapping exercise as a kickoff to build mutual understanding.

- Integrate, Don’t Add: Look for opportunities to weave these activities into your existing curriculum and routines. Use SFBT questioning during student check-ins (“What’s one small thing that’s going a little better today?”). Apply Design Thinking principles to a social studies project where students must solve a community issue. When problem-solving becomes part of the “how” of learning, it ceases to be just another thing “to do.”

By consistently applying these frameworks, you are doing far more than just teaching students how to solve problems. You are cultivating a generation of empathetic communicators, resilient thinkers, and collaborative leaders who can navigate a complex world with confidence and compassion. Each problem solving activity is a step toward building a school and home environment where every individual feels seen, heard, and capable of contributing to a positive solution.

Ready to build a comprehensive, school-wide culture of peace and problem-solving? Soul Shoppe provides dynamic programs, professional development, and hands-on tools that bring these activities to life, fostering empathy and resilience in your entire school community. Visit Soul Shoppe to learn how we can partner with you to create a safer, more connected learning environment.